Second, the capacity to recall information from a voice cue is demonstrably worse than from a face cue. Three empirical methods confirm the relative weakness of voice pathways: First, the recognisability of a voice has been shown to be inferior to that of a face when presented normally, and performance can only be equated when the face is substantially blurred (Damjanovic & Hanley, 2007 Hanley & Turner, 2000).

In addition, good evidence exists to suggest that the voice pathway may be substantially weaker than the face pathway. Importantly, this neuropsychological separation has been demonstrated in behavioural studies, and it is now well understood that whilst faces and voices both contribute to person recognition, they do so via separate parallel unimodal pathways, (see Ellis, Jones & Mosdell, 1997).

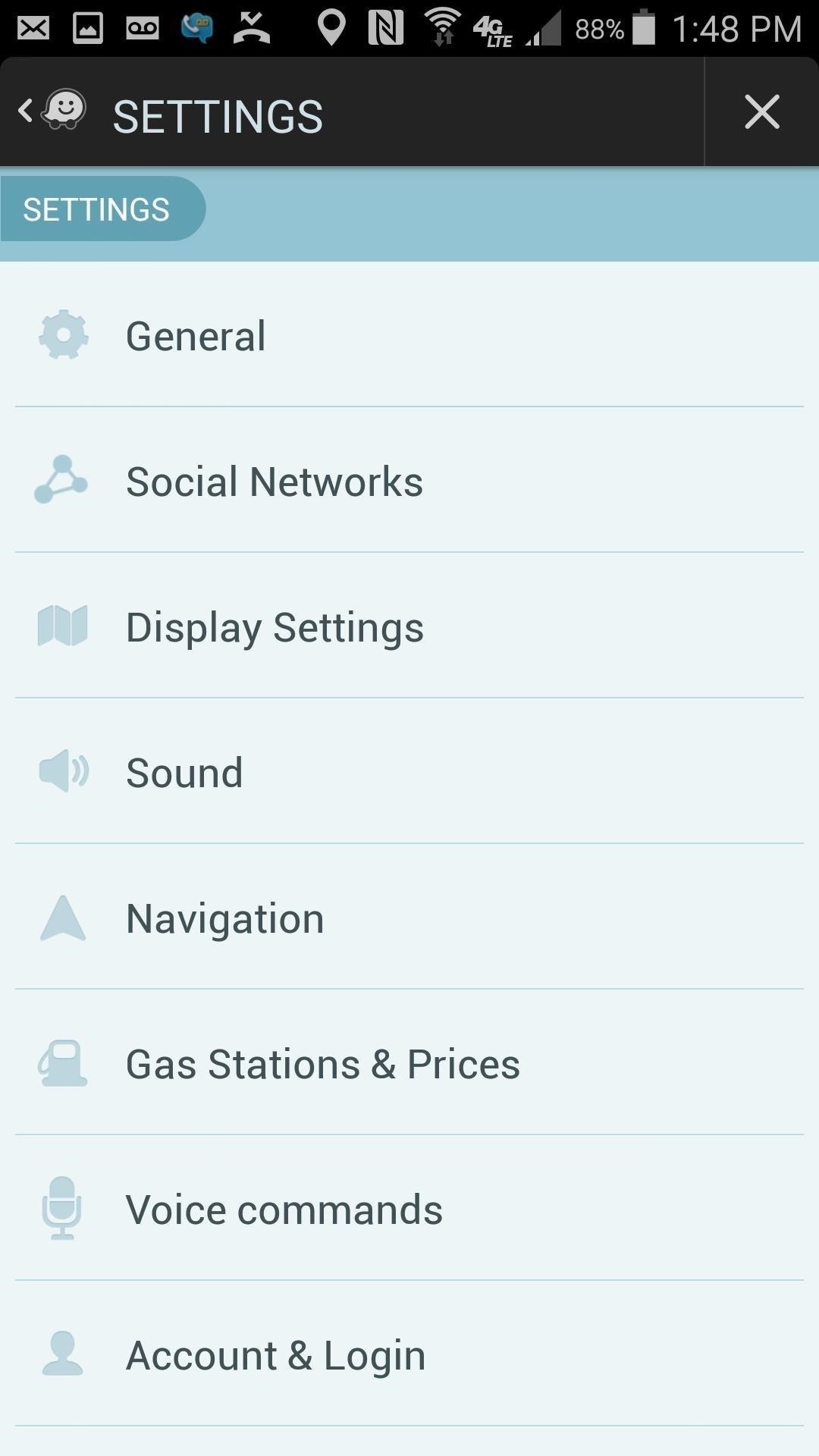

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/003-change-waze-voices-4177124-f9219b518638489fad033497057969b5.jpg)

These areas overlap with, but are separate from, those implicated in face recognition, such that prosopagnosic patients who are substantially impaired in face recognition nevertheless show a spared capacity for voice recognition (Hoover, Demonet & Steeves, 2010). In terms of its location in the brain, fMRI studies reveal several areas involved in voice perception (Gainotti, 2011 Joassin, Pesenti, Maurage, Verreckt, Bruyer & Campanella, 2011 Latinus, Crabbe & Belin, 2011 Love, Pollick & Latinus, 2011). The literature on voice recognition has grown substantially over the last ten years. This provides a test of the suggestion that voices may be weaker, and thus more vulnerable to interference, than faces. The purpose of the present paper is to explore the relative importance of faces and voices through multimodal presentations in which faces and voices are matched or mismatched. Indeed, Belin, Bestelmeyer, Latinus and Watson (2011) present the intriguing description of voices as ‘auditory faces’ highlighting their importance to the process of person recognition. In recent years, attention has become focussed on voices as a means of person recognition. These results converged with existing evidence indicating the vulnerability of voice recognition as a relatively weak signaller of identity, and results are discussed in the context of a person-recognition framework. Moreover, when considering self-reported confidence in voice recognition, confidence remained high for correct responses despite the proportion of these responses declining across conditions. However accuracy of voice recognition was increasingly affected as the relationship between voice and accompanying face declined. Analysis in both experiments confirmed that accuracy and confidence in face recognition was consistently high regardless of the identity of the accompanying voice. The stimuli were face-voice pairs in which the face and voice were co-presented and were either ‘matched’ (same person), ‘related’ (two highly associated people), or ‘mismatched’ (two unrelated people). The results of two experiments are presented in which participants engaged in a face-recognition or a voice-recognition task. The authors would also like to thank Professor Bob Remington for helpful discussions in the early stages of this work, and Emily Gold for her assistance with the collection and piloting of all stimuli. Colleagues on this grant are thanked for helpful contributions to the current work.

Tel: (+44) 2380 592234 Fax: (+44) 2380 594597 email: work was supported by EPSRC Grant (EP/J004995/1 SID: An Exploration of SuperIdentity) awarded to the primary author. Psychology, University of Southampton, UKĬorrespondence may be sent to: Dr Sarah Stevenage, Psychology, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton, Hampshire, SO17 1BJ, UK Sarah V Stevenage* Greg J Neil & Iain Hamlin

Matching and Mismatching Faces and Voices. When the face fits: Recognition of Celebrities from Matching and Mismatching Faces and Voices

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)